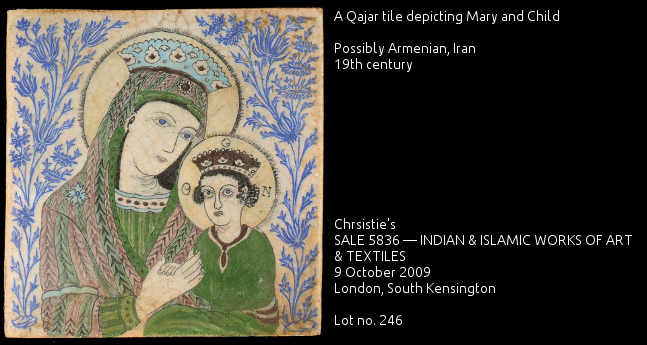

It was Christmas time in the city, and the virtual Twitter city provided wonderful samples of art, sometimes Christian, sometimes Islamic, depicting nativity scenes or Christmas-related subjects. Once again, a tweet reminded me the subtle distinction between Islamic art, Islamicate art, art produced in Islamic lands, art improperly called Islamic Art.

The starting point was a tweet:

I perfectly understand that Mary and Jesus are present in the Qur’an, and that the cultural environment in which the tile was produced was ‘Islamic’, in a sense: the Qajar world.

But even if I am quite ignorant on Qajar art, I asked “Why #IslamicArt?”. The first reply reminded me the long Islamic tradition and the fact that Mary and Jesus appear in the Qur’an. A good reminder of course, but actually I perfectly knew it.

I was primarily referring to the style of the representation, that to my knowledge clearly resembles Byzantine prototypes. If we consider for example the mosaics in Byzantine churches depicting Virgin Mary and the Child, the similarities are pretty clear.

Qajar tiles depicting Mary and the Child

Have I already said that I am no real expert on Qajar art? Anyhow, this tweet provided me with a good excuse to lock the world outside and search the library… which I love! (Thank you @AFatoorechi and @siqilliyya)

Now, the first question that I had was: when was the tile produced?.

Knowing it was sold by Christie’s, I searched old catalogs, to discover that actually, it is not the only instance of a Qajar tile depicting the same scene.

Anyhow this tile was dated by Christie’s to the 19th century, the other three examples I found are dated to the same century or slightly later: late 19th century or early 20th century.

In the other three tiles I found, anyway, the representation of the Virgin and the Child slightly differs from the one of this tile.

Anyway, the prototype, even in these cases should is to be found in Christian tradition, not in the Islamic one.

The position of the two characters, and together with the haloes around their heads are clearly far from the Islamic tradition. Even more, the depiction seems to follow a set standard, with few variations.

This arrangement and iconography can be found, once again, in Byzantine, or anyway Orthodox tradition, where Virgin Mary and the Child, the Theotokos, were depicted with similar features, forming the iconographic type of the Hodogetria.

This type of representation is quite old, of course, and its influence can be seen also in Italian paintings of the Middle Ages, for instance.

Thus, in both cases, the prototypes, or if you like the source of inspiration for the Qajar tiles depicting Mary with the Child, were in any case linked to the Byzantine types.

Not really Islamic so far…

The social and religious context

I believe every work of art is deeply rooted in its own place and period of origin. So why should a Qajar artist depict the Mary with the Child in a Byzantine fashion?

The representation of Maryam and Isa could also be found in Persian tradition. And if we take some examples, it is clear that the iconography is quite different from the one proposed in the tiles.

Anyhow from the Cambridge History of Iran, we learn that during the Qajar period the Christian community in gained a prominent position on the one hand, and that missionaries were active in the region:

“Among the non-Muslim minorities of Iran, the Christians, both Armenians and Assyrians, were able to attain a new position of prominence in government and commerce during the Qajar period. They acted as intermediaries between Muslim Iran and the Christian West, functioning as interpreters, agents of European commercial enterprises, and even furnishing some of the first Iranian envoys to be posted in Europe. […]

Missions – Catholic, Anglican and Presbyterian – proliferated in Iran throughout the 19th century, and found their attempts to convert Armenians and Assyrians from one denomination of Christianity to another more profitable than proselytizing activities among the Muslims. Thus a whole series of ‘native’ churched came into being, at the expense of the Nestorian and Georgian communities.” (pp. 730-731)

Thus, Mary or Maryam?

Should we consider the tiles depicting the Mary and Jesus Christian or Islamic?

It is quite clear now that Christian minority did not suffer exclusion or uncomfortable positions in Qajar Iran, or at least some of them managed to achieve a role in trade and commercial relations with the Christian West. As the Christian community comprised Armenian and Georgian individuals, it is plausible, to me, that the iconographic prototypes used to represent icons was taken from the Orthodox world.

It is difficult to get to a clear conclusion, of course. And the question is always the same: how do we define Islamic Art? In this case, the only strong link between the tile and Islam, according to me, is simply the period and place of origin: Qajar Iran. But if we consider the prototypes, the possible functions of the tiles and the presence of Christian communities that could have used the objects..well… in this case, the tiles are Christian for tradition and function.

Christian art in Islamic setting

From these few remarks, which are not conclusive of course, it is quite interesting to note that tiled with Christian subjects were produced in Qajar Iran, maybe also quite extensively. The fact that they were made in an Islamic setting, makes them Islamic? In this case, not even the style seems to indicate a clear Islamic influence: they may follow the fashion of the period, but they are depicted in a clear ‘Christian’ style.

One last thing…

In the Cambridge History we read also that “Sometimes religious (Christian) subjects were incongruously attempted; the Holy Family in various garbled forms had been a popular theme for mirror-cases since the 18th century” (p. 882)

So far, my knowledge of Qajar art is not wide enough to state with any degree of certainty that these tiles can be part of this category. I would say they don’t, but I do not have enough proofs. Anyhow, whatever the correct answer is, it is clear that the time and place do not suffice to clearly state that a work of art belongs to a particular culture. Many other variables are to be taken into account.

Sources

H. Algar, “Religious forces in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Iran”, in P. Avery, G. Hambly and C. Melville (ed.s), The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 7 – From Nadir Shah to the Islamic Republic, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2007, pp. 705-731.

B. W. Robinson, “Persian painting under the Zand and Qajar dynasties”, in P. Avery, G. Hambly and C. Melville (ed.s), The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 7 – From Nadir Shah to the Islamic Republic, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2007, pp. 870-889.

I found some of these tiles in Israel in a small shop off the beaten path and under a stack of other tiles. Could I send u a picture to see if you think they are authentic?

LikeLike

Hi Will! Sure, send them over via email. I’m no expert in tiles but will be happy to have a look!

LikeLike